This article has been guest-authored by Ruan van Rensburg, consulting actuary and founder of Lux Actuaries.

The UAE’s introduction of the voluntary End-of-Service Benefits (EOSB) Savings scheme presents companies with crucial decisions regarding their end-of-service benefits. This article has been drafted as the first of a series that touches on the key issues that need to be considered. There is some time before this switch is made compulsory which should allow employers to fully consider all implications before a decision is made.

This article lays out the background and answers the following question: Is this new scheme better or worse for employees? In short, it depends!

Understanding the two schemes

The current EOSB Gratuity scheme operates as a Defined Benefit (DB) scheme. Under a simplified example, an employee with 10 years of service is entitled to a lump sum of approximately 8.5 months’ salary. Importantly, this calculation uses their salary at the end of the 10-year period, meaning the benefit increases with annual salary increases. This creates a liability on the company’s balance sheet.

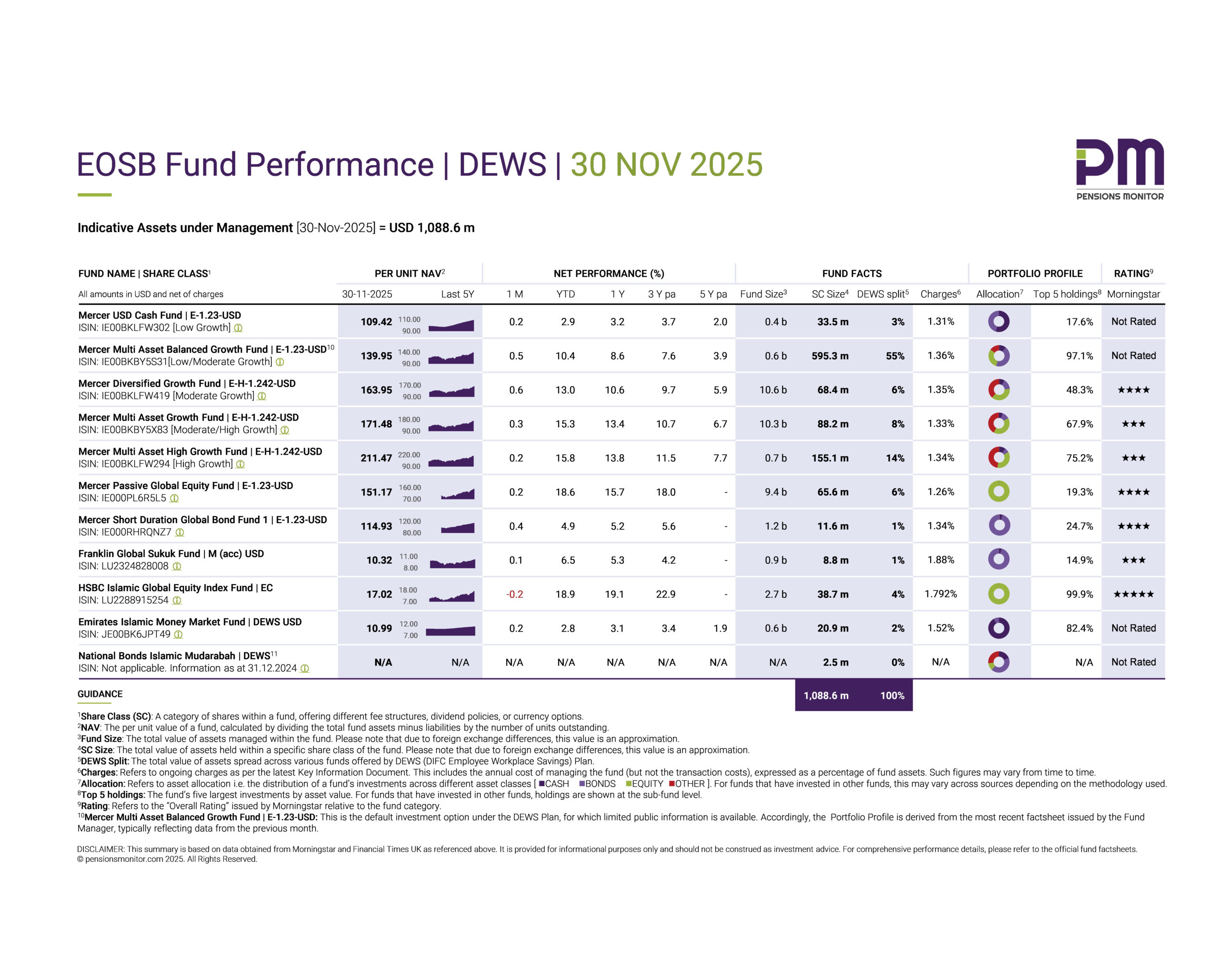

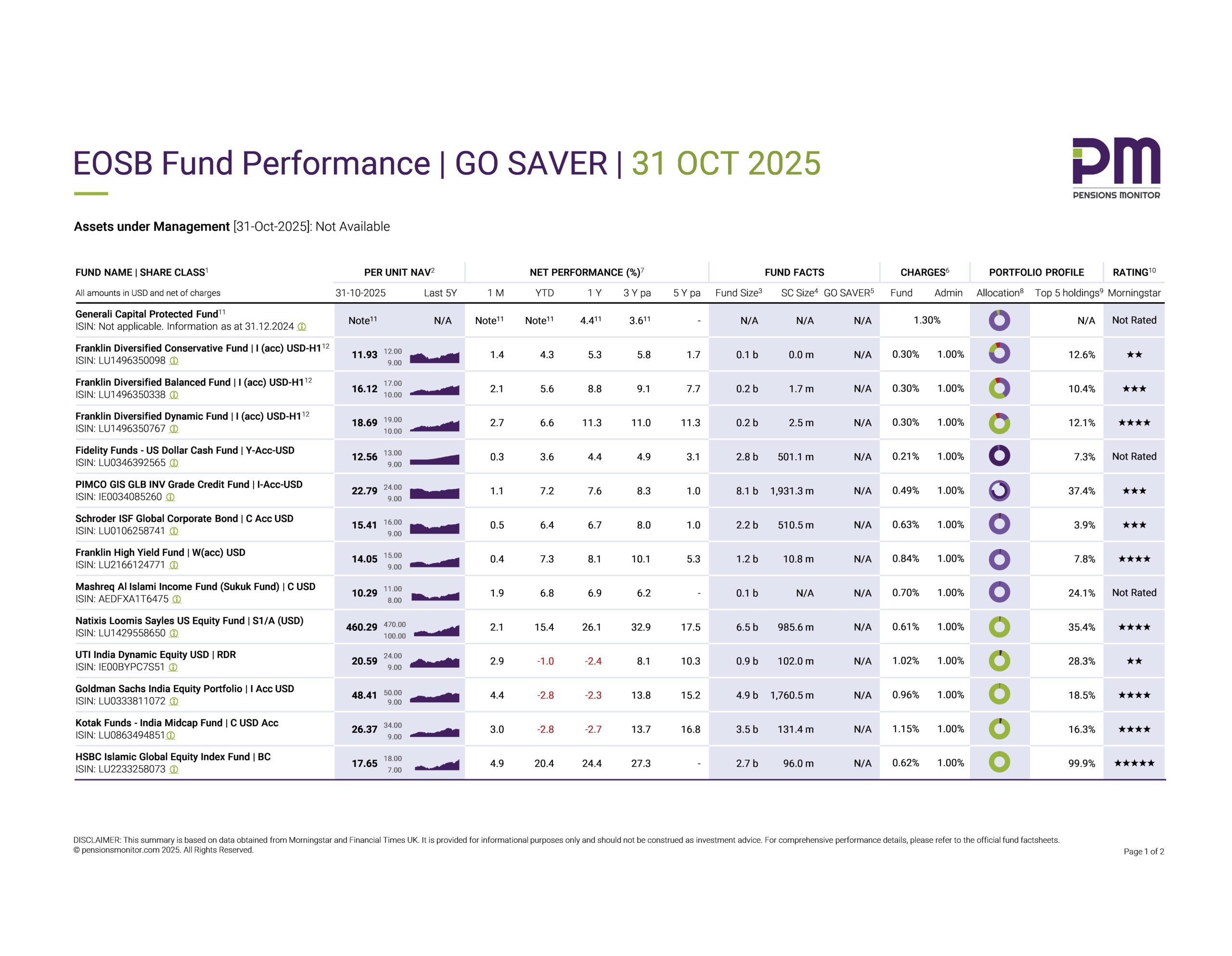

The new EOSB Savings scheme, likely to become compulsory by the end of 2026, is a Defined Contribution (DC) scheme. It mandates monthly contributions of 5.83% of salary for the first 5 years, increasing to 8.3% thereafter. These contributions accumulate in a savings account, aiming to generate investment returns for the employee. Unlike the EOSB Gratuity scheme, there’s no defined benefit – the final lump sum depends on the investment performance.

Benefit implication

For employers, the EOSB Gratuity scheme presents certain challenges. Employee salary increases directly impact the benefit amount, even for benefits earned in earlier years. This system effectively means employees are financing their employer, creating a risk for both parties. The employer bears the risk of finding the cash to pay the lump sum upon the employee’s departure, while employees risk losing their benefit if the company faces bankruptcy.

The new scheme shifts the risks. Employers face a guaranteed monthly cash flow expense for contributions, replacing the previous “pay-as-you-go” system upon employee departure. However, they avoid the increasing liability associated with salary-linked benefits and eliminate the risk of struggling to meet lump sum payments if multiple employees leave simultaneously.

The first major implication is that employee benefits are held securely, and ring fenced from an employer’s balance sheet. This is in line with international practice, and is a major advantage to the new system. In the event of a corporate default, an employee’s accrued benefits are secure.

The second implication is that employees are now exposed to the risks and rewards of investment markets. This may result in actual benefits being greater than or less than those accrued under the old system.

The graph below shows a comparison of the accrued benefit under both systems. The changing variable is the investment return assumed on the EOSB Savings scheme. Importantly, this is the investment return net of all EOSB Savings fees. Also, these are long-term averages, and the point we are trying to convey is that if your long-term compound investment return is lower than your long-term compound salary increases, then you lose in the new scheme. You should consider what you think your long-term average annual salary increase will be, and beat that return (within acceptable risk parameters) while contributing to the new scheme.

Orange: Current EOSB Gratuity scheme

This is a simple example. Salary escalation/compounding happens monthly, and so do investment returns, using (1+g)/(1+i). Salary at the start is AED 10,000 per month, and salary escalation g is 3% per year, and investment returns i are taken as either 2%, 3%, 5% or 10% per year.

For this particular person, given that their long-term salary increases are 3% per annum compound, earning anything less than 3% per annum compound in investment return in the new savings scheme, will leave them in a worse position compared to the current gratuity scheme.

From an investment perspective, the merits depend on various actuarial factors such as the employees age and expected salary scale progression, and investment prospects. What we have seen launched thus far is capital-protected products for lower income employees. The key consideration is how the net return expected on such products compares with inflation, and salary inflation. Some of these products guarantee a result lower than what is expected under the existing system.

Ultimately, employers must carefully assess the financial and strategic implications of all decisions, seeking expert advice to ensure that employee savings are treated with the due care and diligence required to avoid reputational and legal liability.

Another key issue relates for the scope for inadvertent transfers of value between employers and employees regarding the accrued benefits. Without due consideration, employers may pay up to 1/3rd more or less than that which is actuarially fair, to the benefit or detriment of employees. The next article in the series deals with these questions and fairness to the Employer.

Editor comment

We at Pensions Monitor would like to express our gratitude to the guest author of this interesting thought-piece, Mr Ruan van Rensburg, consulting actuary and founder of Lux Actuaries. In case of questions on this article, or anything related to Employee Benefits or the new End of Service Benefit Saving schemes, please contact Ruan directly on ruan@luxactuaries.com.

In case you, dear Reader, have some interesting views,or thought-provoking takes on the newly emerging End-of-Service Benefit Savings market, then please get in touch with us on info@pensionsmonitor.com – we will gladly consider publishing your article on our site.