As we approach the second anniversary of Cabinet Resolution 96/2023 that introduced the alternative End-of-Service Benefits (EOSB) Savings Scheme, a question looms for companies that already offer some form of private pension or savings plans: Is it possible to get an exemption from this national scheme once it becomes compulsory?

To be clear: As of now, there is no regulatory guidance on this question as the scheme is still voluntary. However, sooner or later, it is expected to become mandatory. So, for companies that have already taken proactive steps to support the long-term financial wellbeing for their employees, this is a question worth exploring now.

What are these private pension plans?

Some companies in the UAE already offer structured pension or savings plans. These are often well-designed, well-governed, fully funded plans that usually offer better benefits than the current gratuity system (they are never less than the mandatory gratuity as they feature a built-in minimum benefit underpin equivalent to the gratuity benefit). Employer contributions often exceed the minimum gratuity target equivalent of 21 or 30 days per year of basic salary, mandated under UAE Labour Law, sometimes reaching even 15% of basic salary per month or higher.

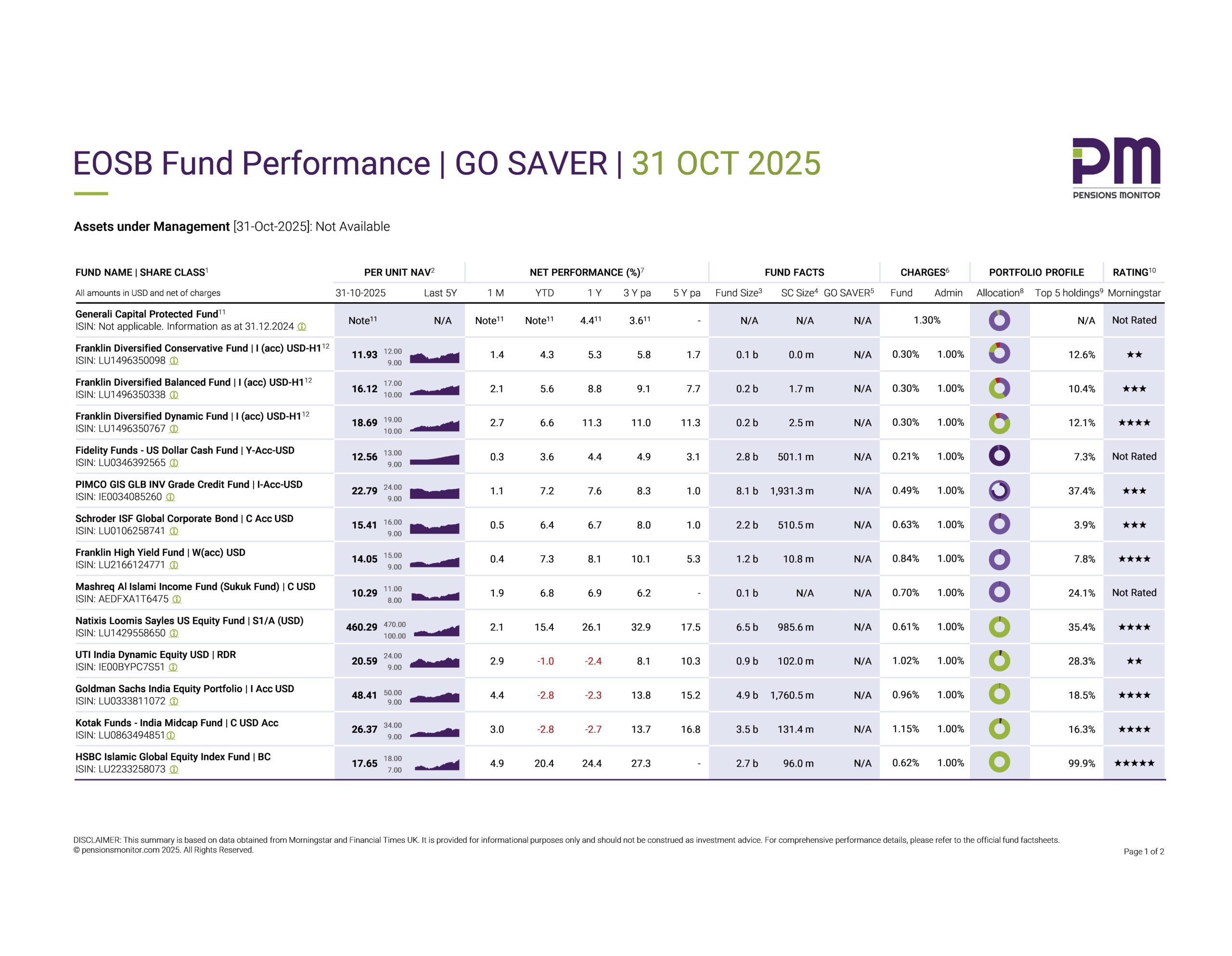

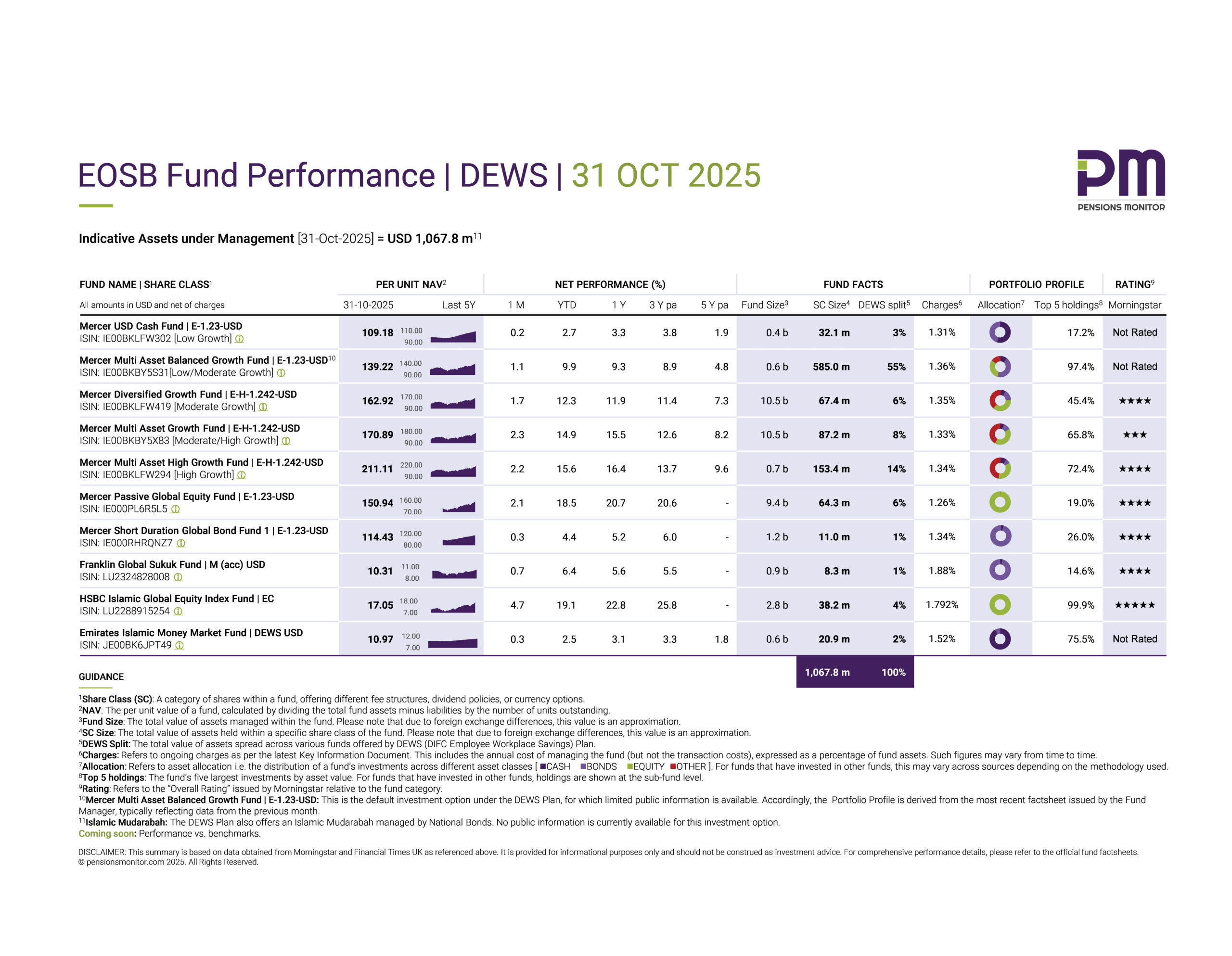

In particular, multinational companies for over 30 years have been offering International Pension Plans (IPPs) and International Savings Plans (ISPs) to standardize benefits across their global operations or to provide retirement benefits in markets where local solutions are either unavailable or deemed inadequate or to protect employees by globally funding gratuity benefits in an effective secure vehicle. These IPPs commonly offer access to a broad range of institutional-grade investment funds at low cost with fund management fees sometimes absorbed by the employer, in part or in full.

According to the most recent Willis Towers Watson (WTW) IPP Survey 2024, over 100 mid- to large-sized multinational companies in the UAE currently offer global or regional IPPs to their staff. So, this isn’t a niche issue, as it will affect thousands of employees from many high-profile employers once the UAE’s EOSB Savings Scheme becomes mandatory.

Let’s look at pension scheme designs

(The information below is compiled from five IPPs and ISPs offered in the transport sector where IPPs are common. Source: WTW IPP Survey 2024)

Across the transport sector, there are long running well-established supplementary savings schemes that have been and are currently offered in the UAE and regionally, aimed at all or key expatriate staff.

How these work:

- Participation is often a condition of employment and automatic after three to six months of service.

- Both employees and employers typically will contribute to the scheme each month:

- Employees will contribute 3% to 5% of their basic salary; and

- Sponsors contribute at least 8% (the gratuity equivalent rate), often up to 12% and rising based on service to up to or even exceeding 15% of basic salary.

- Assets are pooled and each employee’s account is separately earmarked and identifiable.

- Low cost institutional investment funds are offered from global fund managers across various asset classes.

- Employees make their own investment decisions across a diversified fund range based on the membership demographics of the scheme (Shariah investments are growing rapidly).

- Each scheme is set up under a trust in offshore locations, such as Guernsey, Jersey or the Isle of Man according to their local Trust Law, offering strong governance and oversight, as well as protection from employer insolvency.

- Vesting rules are common and apply to the employer contributions only. Employees are entitled to:

- A scale leading to a proportion of employer contributions vesting for between 1-5 years of scheme membership; and

- 100% after five years of membership.

- But each scheme also includes a minimum EOSB gratuity guarantee or underpin as per the UAE Labour Law.

At the time of separation, employees receive either their vested balance or the statutory EOSB gratuity, whichever is higher. This ensures that the conditions set out by the UAE Labour Law are fulfilled in all circumstances, and no employee is disadvantaged by the scheme, even if investment returns are poor.

You may wonder, why employers bother with IPPs such as these, if they anyway guarantee the minimum statutory gratuity? A key reason is employee attraction and retention. Firstly, and as explained above, in most cases employees will receive a significantly higher benefit compared to the basic entitlement under the Labour Law. Secondly, the built-in vesting schedule encourages employees to stay longer with companies. And then there’s also competitive industry pressure – for example, IPPs are commonly offered across the transport sector.

Should the UAE government allow exemptions?

There are strong arguments in favour of allowing companies to opt out if they already have a suitable pension or savings scheme. Particularly, if the existing plan offers equal or better terms for employees than the national scheme, and if the company has already invested in a well-governed structure with regular contributions and long-term vesting schedules, then a forced transition to the national scheme will be disruptive and costly. Furthermore, it will complicate matters as employers might still want to offer a scheme that is superior to the new EOSB Savings Scheme.

“Looking at other governments in the recent past is helpful too. The UK and Poland both have had mandatory auto-enrolment in place for a number of years now and both chose to grandfather certain existing arrangements already being offered (but obviously with minimum contribution levels). This was to avoid disruption to those paternalistic employers that were already acting in the best interests of their employees by providing more generous benefits than were mandated by law.”

— Michael Brough (A global pensions specialist at WTW and author of the WTW IPP Survey since its outset nearly 20 years ago.)

But there are also good reasons for regulators to be cautious about exemptions. Not all private plans are equally well-managed or adequately funded and may potentially put employees’ savings at risk. Besides, allowing opt-outs will make supervision and data collection more difficult for the regulators. A solution might be to allow exemptions but keep the historical underpin of 21 and 30 days as a minimum leaving service test, applicable only for those exempted schemes. That would remove the need for arduous regulatory oversight and move the responsibility to auditors and actuaries.

What can we learn from the DIFC?

The Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) introduced its own mandatory EOSB Savings Scheme in 2020. And it does allow companies to apply for exemption, provided their own schemes meet strict criteria. For example, a company must show that its alternative savings scheme is:

- Funded: Contributions must be paid monthly, not promised at the end.

- Regulated and well-governed: The scheme must have an independent trustee, clear reporting, and proper administration.

- Equal or better value: It should offer benefits that are comparable or superior to the DIFC scheme.

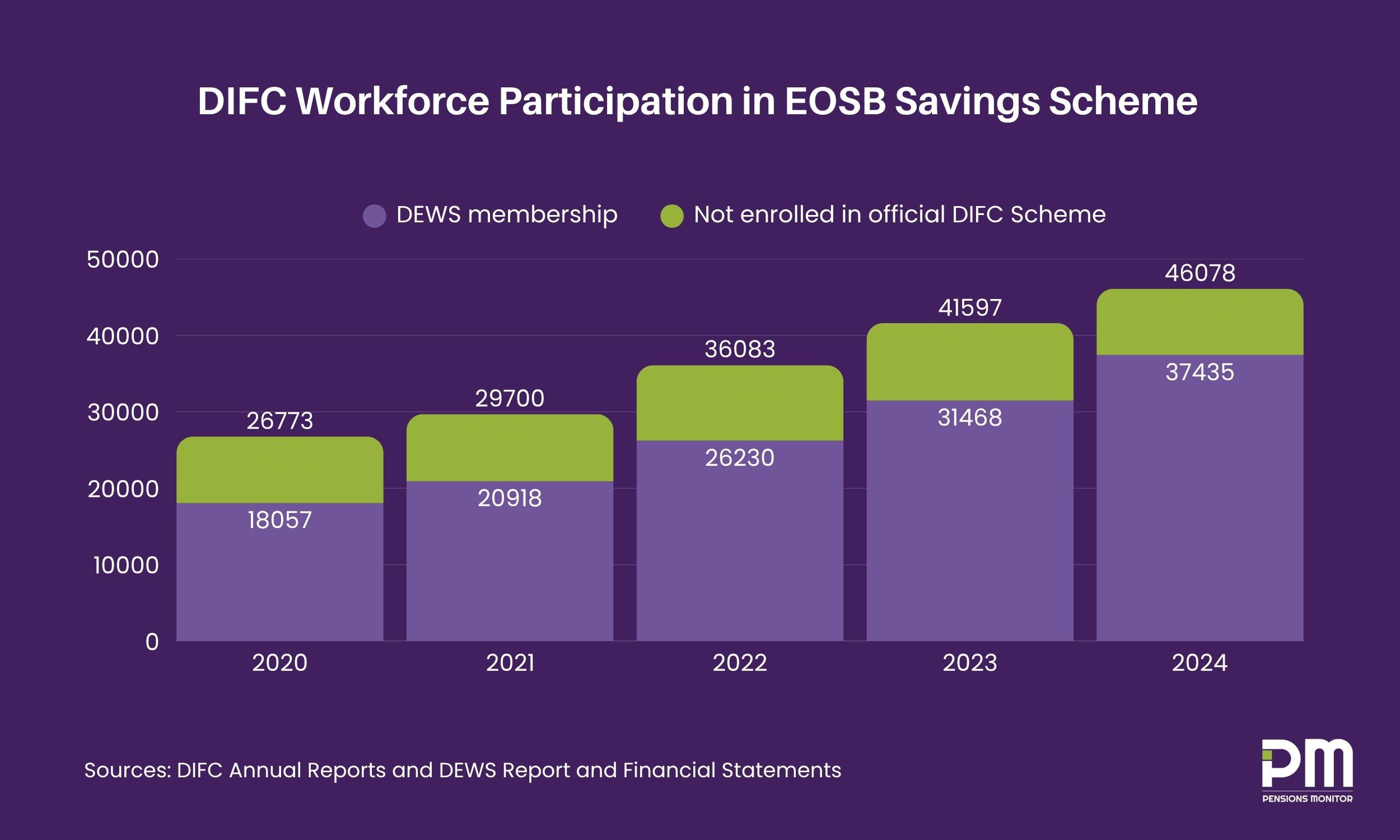

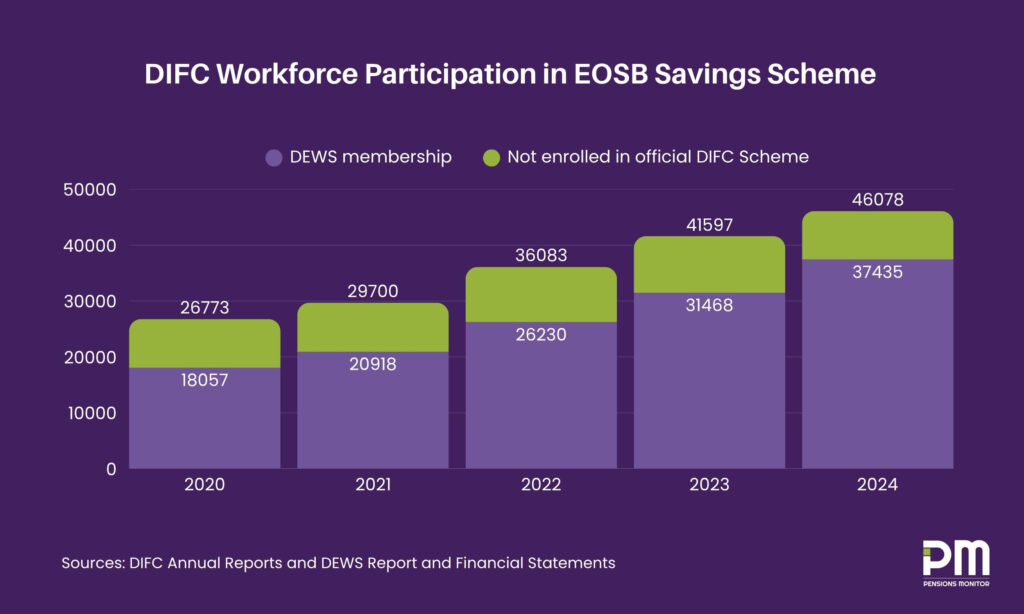

A quick review of DIFC workforce figures over the years shows that, year-on-year, between 8,000 and 9,000 employees have not been enrolled in DEWS — the only official scheme in DIFC from 2020 to 2024. This likely reflects a combination of both exemptions and ineligible employees, such as UAE and GCC nationals, among other categories.

But while DIFC’s total workforce has grown over the years, the number of employees not enrolled in DEWS has remained relatively flat, bringing the non-enrollment rate down from 33% in 2020 to just 19% in 2024. This trend suggests that most exemptions were likely granted early on, when DIFC’s scheme first became mandatory. Companies that joined the DIFC later may not have set up their own qualifying schemes or may not have been approved for exemption from the official DIFC scheme – and of course, some non-enrolled employees are simply ineligible under the rules.

What might happen for mainland UAE?

As of now, we don’t know if similar exemption rules will be introduced for mainland UAE companies (and by extension, most of the non-financial freezones). But if the UAE government does decide to allow exemptions from the national scheme when it becomes compulsory, there’s a good chance it will follow a similar path to the DIFC, where:

- Clear proof of governance, funding and value will need to be demonstrated;

- Strict criteria will apply to protect employees;

- Possible minimum benefit tests as a condition of exemption, and

- The regulator will reserve the right to independent oversight.

But until the rules are announced, this remains a “what if” scenario that many HR leaders are already thinking about. So, in the meantime, here’s what you can do to prepare:

- Review your current scheme to ensure it is well-governed, fully funded, and independently managed. Would it meet the exemption criteria used in the DIFC?

- Assess whether it offers equal or better value than the national scheme?

- Maintain a clear documentation trail to support your case, should an exemption application process be introduced.

Having this information ready will place your company in a strong position, whether you’re transitioning to the national scheme or applying for exemption once the rules are announced.

If exemptions are not permitted, companies will be required to make statutory contributions into the national scheme. Any surplus contributions can still go into your existing pension scheme, preserving the value of your broader employee benefits strategy, although this may not be ideal.

At Pensions Monitor, we’ll continue tracking this space and share updates as soon as regulatory guidance becomes available. Sign up for our free newsletter to stay informed.